Casio Cz 101

GForce’s Jon Hodgson has been a long-term fan and still owns a CZ-101 and a VZ-8 (which uses a very different synthesis method to the CZ series). Here’s his take on the CZ. Subtractive Digital Synthesizers are a silly idea, the classic Moog 4-Pole filter needs 10 transistors in analogue form - A 4-Pole audio-rate digital filter takes hundreds. Add a couple of oscillators and you're probably into thousands, and that's before you even start trying to do the cool stuff, like the distortions that make real analogue filters sound so nice, or oscillator sync.

It's small, it's cheap, and it's good! This is the pea-size version of the CZ-1000 with a mini-keyboard. The CZ-101 is a digital synth and although the programming is. It's small, it's cheap, and it's good! This is the pea-size version of the CZ-1000 with a mini-keyboard. The CZ-101 is a digital synth and although the programming is. CZounds Casio CZ synth patches are inspired by 1980s. Punchy horns, rich pads, sweeps, effects and retro flavor galore. Compatible with Casio CZ-1, CZ-101.

These days processors with millions upon millions of transistors sell for very little, so we can implement these very inefficient designs if we want the sound, but back in the early eighties things were very different. The processing power required to implement even a monophonic digital subtractive synth would have been prohibitively expensive (not so much home recording as sell-your-home recording), so manufacturers needed a different approach. The most famous and successful was Yamaha's FM synthesis. Six sine waves (four on the DX9), modulating each other according to various algorithms.

The success of this technology was overwhelming, and was not seriously challenged until the end of the eighties with Roland’s D50, and Korg’s M1. There was another contender though.

Sapphire Asset Management Tool there. When Casio were looking for a solution FM synthesis (actually it should have been called PM, since it was phase modulation rather than frequency) was almost right, there were only three things wrong with it: • It was still quite complex to implement, and therefore quite expensive to implement. That was fine for Yamaha aiming for the pro market, but not for Casio who were aiming more at the consumer market.

• It was hard to use, it's quote hard even for experienced programmers to predict what the effect of changing something on an FM synth will be. • Most importantly, Yamaha owned all the patents!

So Casio came up with a related, but computationally simpler system, called Phase Distortion. Aside from being free of Yamaha patents, and being simpler and thus cheaper to implement, PD had the great advantage of actually being quite similar to analogue subtractive synthesis when it came to programming. For example, the effect of the DCW envelope is not quite the same as the effect of a Filter envelope, but it is close enough that if you can program one, you can program the other. Of course learning how to get the best out of either takes a little longer.

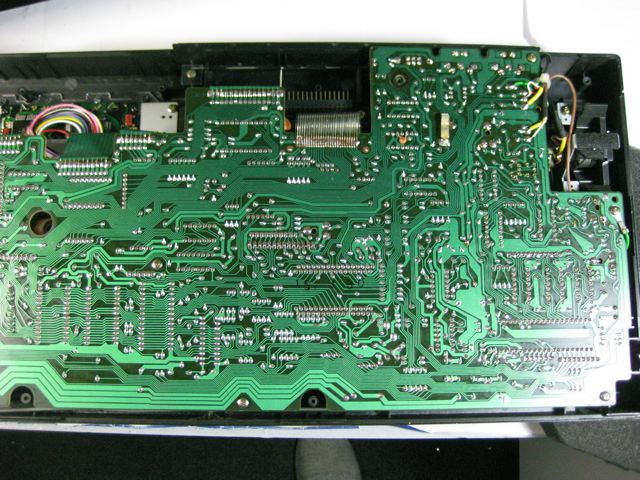

There are a number of articles on how phase distortion works, so it isn't worth going into here. Technically speaking though, it is a very neat solution. It manages to extract a wide variety of useful and accessible sounds out of the minimum gate count, in fact if the history of electronic synthesis in a parallel universe started off with digital synthesis rather than analogue, I wouldn't be surprised if the CZ101 (or maybe the version with a full sized keyboard, the CZ1000) was their equivalent of the Minimoog. The CZ-101 looked like a toy, with a plastic case and mini keys. But with six eight stage envelopes, dozens of waveform shapes, ring modulation and multi-timbral operation, it didn't have to sound like one.